Exhibitions I have curated, co-curated and produced.

KIJK at Kunstinstituut Melly

30 April —1 September 2024

“Kijk” (Look), says Paul, as he takes out the pencil from his pocket. Just like that, the unsolvable problem you brought to him is figured out, with a drawing, a call, or a thing he has seemingly held onto for this exact moment. Paul van Gennip has worked for over 34 years at Kunstinstituut Melly as Deputy Director. As he retires, the book PAUL delves into his legacy, focusing on the everyday aspects that reflect his determination to make art happen.

Paul’s long-time colleagues, line kramer and marjolijn kok, who together form THE KOKRA FAMILY, were commissioned for the book to document the vast collection of objects Paul has accumulated at the institution over the years. They spent over a year developing the project, selecting and documenting more than 500 objects. A selection of this photographic series, accompanied by descriptions authored by Paul, is displayed in the exhibition. A few items from his collection are presented in their original form: as ‘things’. From a charred fuse to a chair from the (1995) exhibition of Paul Thek, these objects symbolize the institution's exhibition history

The exhibition is curated by Julija Mockutė in collaboration with THE KOKRA FAMILY and Paul van Gennip, with the assistance of Alexis Medina Trejo. Special thanks to 75B, Wendy van Slagmaat-Bos, Tubelight, and Jordy Walker.

My Oma at Kunstinstituut Melly

8 December 2023 —1 September 2024

My Oma is a curatorial project focusing on the figure of the grandmother. The project overall explores personal and cultural legacies mobilized by affection as much as by conflict. It convenes artists and narratives, as well as artworks and theory that articulate central issues of our time: experiences of immigration, dissonant heritage, and changing gender roles.

My Oma gives special attention to embodied knowledge and micro narratives. In the light of increasing political polarization, My Oma promotes historical learning, strengthened intergenerational bonds and celebrates knowledges held among diaspora communities. The bilingual title—with the English my and the Dutch oma for grandmother—is meant to communicate this personal approach. As such, we address grandmothers as plural protagonist imbued with agency as well as being the subject of social projections. The figure of the grandmother thereby allows for various approaches to histories, traditions, and ancestry. It also welcomes the reconsideration of gendered and ageist determinations surrounding cultural and material legacy.

Organized by Kunstinstituut Melly, My Oma involves a large group exhibition of contemporary art including new commissions, existing work, performances, and events. Participating artists are: A Maior (Portugal), Funda Baysal(Turkey), Yto Barrada (France), Meriem Bennani (Morocco), Nurul Ain Binti Nor Halim (Thailand), Lia Dostlieva and Andrii Dostliev(Ukraine), Shardenia Felicia (Curaçao), Susanne Khalil Yusef(Germany), Charlie Koolhaas (The Netherlands), Liedeke Kruk(the Netherlands), Marcos Kueh (Malaysia), Berette S Macaulay(Sierra Leone), Silvia Martes (Curaçao), Hana Miletić (Croatia), Jota Mombaça (Brazil), Sheelasha Rajbhandari (Nepal), Anri Sala(Albania), Stacii Samidin (the Netherlands), Kateřina Šedá (Czech Republic), Julia Scher (United States), Buhlebezwe Siwani (South Africa), Judy Watson (Australia), and Sawangwongse Yawnghwe(Shan State, Burma).

During the opening weekend, from December 8th to 10th, a number of performances and presentations took place at Kunstinstituut Melly under the name of Show and Tell: Ola Hassanain (Sudan), Yoeri Guépin (The Netherlands), Melike Kara(Germany), Raimundas Malašauskas (Lithuania), Amanda Moström (Sweden), Maria Pask (Wales), Laure Prouvost (France), Sara Sallam (Egypt), and Asa Seresin (United Kingdom).

My Oma is the closing exhibition and public-engagement project of Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy’s tenure as the director of Kunstinstituut Melly. It marks her six years of transformational institutional work here. The exhibition and its parallel projects result from curatorial research and public outreach conducted by her and her team—including curators Rosa de Graaf, Jessy Koeiman, Julija Mockutė, and Vivian Ziherl—during this span of time. Curatorial advisors to My Oma include: Diana Campbell(chief curator Dhaka Art Summit, Bangladesh), Edward Gillman (director Auto Italia, London, UK), Sun A Moon (director Space AfroAsia, Dongducheon, South Korea), and Manuela Moscoso(director CARA, New York, USA).

Falke Pisano:

not

to be

governed like that

by that at Kunstinstituut Melly

9 June — 19 November 2023

For her project-based exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly, artist Falke Pisano presented a new work that stemmed from her year-long research into the first savings bank in Rotterdam. Established in the early nineteenth century, the Savings Bank in Rotterdam (Spaarbank te Rotterdam) was created by a group of affluent residents and an emerging local bourgeoisie. Some of the people involved in this bank’s foundation were related to the Society for Public Welfare (Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen), which, for its part, had been established a few decades earlier, in 1784. The purpose of this foundation was to stimulate personal growth and self-discipline amongst working-class citizens and those who were financially underprivileged. The foundation saw the dissemination of “virtue” as a way to mend a divided society. The opening of Spaarbank championed this belief, too.

The artist explains that, through her research, she came across the so-called bourgeois “civilizing offensive” of the 19th Century, and that she was able to place the history of the Savings Bank in context. “I focused largely on the way common values and worldviews of the upper classes were conveyed through administrative language,” she says, “which I found future-oriented and patronizing, and, as such, disruptive and transformative of social relations and institutions.”

In her new work, not / to be / governed like that / by that, Pisano straddles the legacy and contemporary currency of such viewpoints and language around poverty prevention. The centerpiece of Pisano’s installation was shaped after a typical boardroom table. The tabletop was made up of seven separate panels, each with unique screen-printed illustrations underneath. These illustrations showed actions, spaces, and moments of exchange, crisis, and control. While at first concealed, the illustrations were revealed during scheduled performances by Pisano, where she used them to deliver different narrations. This also meant that, formally, the artist’s performance involved overturning the sculpture’s main surface, and thus the purported function of a table connoting decision-making power.

Falke Pisano not / to be / governed like that / by that was curated by Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, and organized by Julija Mockute.

Lucy Beech: Ooze at Kunstinstituut Melly

9 June —19 November 2023

While much attention is paid at present to how society creates waste, Lucy Beech is preoccupied with how waste shapes society. The latest works by the visual artist and filmmaker consider ways in which the uses of waste, for example in the context of science and fiction, have come to “blur boundaries between social constructs and biological realities.” They probe both real-life and imaginary experiences that expand on understandings of gender, desire, and at times, crisis. The artist’s solo exhibition, Ooze, presented their new film Flush, commissioned by Kunstinstituut Melly. It also included the Dutch premiere of Beech’s Warm Decembers (2022), as well as their earlier work, Reproductive Exile (2018).

To create these films, Beech corresponded with historians, poets, and doctors as well as shadowing specialists in waste management and reproductive science. They focus in particular on waste matter that does not easily fit into a single category nor field of research and production. A common thread throughout the moving images presented in Ooze is the probing of ideas about waste, value, gender, and productivity, as much as the reproductive links between them.

Beech, who was born and raised in the UK, has just completed a two-year fellowship at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Located in Berlin, where Beech lives and works, the focus of this research institute is on “scientific thinking and practice as historical phenomenon.” There, the artist’s research gave special attention to the relationship between bodily waste and reproduction processes. Beech also created the research group Working with Waste, composed of artists, scientists, and other practitioners. But while Beech conducts rigorous research, and while some of the experiments featured in their films are real, the work of their artistic practice falls decidedly into the category of speculative fiction. The artist champions the hypothetical and generative “what if?” that art, creativity, and science share.

The films presented in Ooze were shot by Beech in 4K and include surround sound. At Kunstinstituut Melly, the experience of these films’ lush images and sound was heightened by insulated, darkened galleries. To realize this exhibition, Kunstinstituut Melly collaborated with two institutions in Germany: Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst in Oldenburg and Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof in Hamburg.

Lucy Beech: Ooze is curated by Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, with curatorial assistance by Julija Mockutė.

Pablo Castañeda: Border Autofictions at Kunstinstituut Melly

9 September —31 December 2022

Border Autofictions included over forty paintings, from 2006 to date, by the Mexican artist Pablo Castañeda. It also presented a new mural painting created by the artist on-site. This was Castañeda’s first solo exhibition in Europe. Urban micronarratives, absurd and surrealist scenes, and desert landscapes figure extensively in the artist’s work. At times, his paintings are composed like misè-en-scene for film noir. Other times, these are composed as miniature panoramic narratives or appear as fragments of larger frieze paintings. In this exhibition, Castañeda’s work was grouped in different types of scenarios, rather than chronologically or by the artist’s painting series. This arrangement is to emphasize the source of the painting’s imagery and what these images narratively, and even cinematically, emulate within a composition.

An artist living in Mexicali in Baja California, Mexico, Castañeda has for decades focused on picturing his immediate environment and surrounding landscape, his friends, and the local arts community. Like many artists, his knowledge and trajectory in the art field has been shaped through a combination of curiosity and discipline, and not through professional or academic degree-granting programs. Instead, kinships formed through lived experiences, self-organized art workshops, and intellectual affinities have been his primary forms of schooling.

The exhibition title, Border Autofictions, alludes both to the artist’s context, as much as to his milieu figured in this work. The artist’s hometown, Mexicali, borders Calexico in California, USA. These so-called twin cities are part of a desert valley. South of the border, Mexicali’s century-long development has been heavily influenced by a binational water treaty, first, and, decades later, by an international trade agreement. While the former allowed agronomy and agricultural development (its sustainability, questionable), the latter embedded an international manufacturing culture, which, while creating employment, has deepened economic inequality in the region. In any case, both kinds of development have been reasons for emigrants to settle in this arid land. Another reason for settling in Mexicali has been the impossibility of crossing the border into the ‘land of opportunities’ that the US has been considered by too many and for too long.

Kunstinstituut Melly’s director, Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, is the curator of this exhibition. The exhibtion was produced by Julija Mockutė.

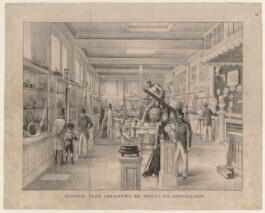

Rotterdam Cultural Histories #20: The Museum of Education and Art at Kunstinstituut Melly

1 October 2021 —1 May 2022

The twentieth edition of Rotterdam Cultural Histories was a documentary display about the Museum of Education and Art sited on Witte de Withstraat from 1880 to 1884. This short-lived museum in Rotterdam was located just a few steps away from Kunstinstituut Melly’s building, which, for its part, was constructed in the 1870s as an all-women civic school.

The Museum of Education and Art was founded by the Rotterdam publishers J. van der Hoeven and D. Buys. Their approach to the educational vocation of museums was peculiar, or certainly more entrepreneurial and less sacred than we deem so today: on the one hand, the museum's exhibitions presented artistic, scientific, and pedagogical materials; on the other hand, these exhibitions also functioned as commercial displays, since its many items were for sale. This two-fold purpose promoted art as tools, and that learning could be done in a newfound context.

Documentary, immersive, and small in scale, this exhibition presented materials of the Museum of Education and Art drawn from Stadsarchief Rotterdam, including an 1880s neighborhood map; the museum brochure, promotional materials, and floor-plan, as well as pages of the inventory for sale of the museum's collection.

Rotterdam Cultural Histories #20: The Museum of Education and Art is organized by a team at Kunstinstituut Melly: Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, Julija Mockutė, Paul van Gennip, Wendy van Slagmaat-Bos, and Jeroen Lavèn.

Iris Kensmil: Some of My Souls at Kunstinstituut Melly

1 October 2021 — 20 March 2022

For more than seventeen years, Iris Kensmil's artistic practice is committed to positioning the experience, activism, and intellectual work of Black people in the Western World as a central pivot to modernity’s emancipatory aims, or, as it were its progressive claims. She does this through a practice that involves studying, archiving, and painting; through a quiet exercise of reading, listening and looking. Over the years, her work has more and more focused on depicting counter-narratives to modernity by Black thinkers and activists in the “West” from the twentieth century to date. Stylistically, she found a way to break with how Black people, and especially women, have been typically painted. Instead, Kensmil presents them, in her words, "as the intellectuals they are."

Raised in Suriname during her early childhood, Kensmil was born in Amsterdam, where she currently lives and works. Her solo exhibition at Kunstinstituut Melly consisted of a new body of work about the Netherlands. This was set in dialogue with a selection of paintings and drawings from 2007 to date regarding the artist’s longstanding interest in music—especially protest songs, from Blues to Soul and that inspired by African American emancipation struggles. In creating her work, Kensmil not only traces or captures personal and historic transnational experiences. She also portrays communities, events, and aesthetic forms that manifest what the scholar Paul Gilroy identifies as an “embattled cultural sensibility, which has also operated as a political and philosophical resource.”

The exhibition was curated by Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, with the assistance of Julija Mockutė.

84 STEPS at Kunstinstituut Melly

9 April 2021 —24 September 2023

Inaugurated in 2021, 84 STEPS featured projects conceived at the intersection of art and education. 84 STEPS occupied an entire floor of Kunstinstituut Melly. It featured a constellation of specially commissioned artworks and environments. The installations were regularly activated in different ways by the participating artists, as well as the institution's programming team and guest participants. The work and events within 84 STEPS gave special attention to the relation between physical and mental architectures, as much as with interpretations of personal and social health. These relations have been actively explored through programs organized in seasonal thematic clusters.

The name 84 STEPS alludes to the number of steps that connect the building's ground floor to this third-floor gallery. This transformation of a white-cube gallery into a dynamic space for socializing art follows Kunstinstituut Melly’s 2018 makeover of the ground floor gallery, MELLY. This approach to exhibition-making emphasizes an ongoing interest in developing new forms of public engagement with art, and no less of articulating embodied knowledge and shared experiences with art.

To date, 84 STEPS has included works by Afra Eisma, The Feminist Health Care Research Group (Inga Zimprich), Alma Heikkilä, Maike Hemmers, Moosje M Goosen and Daily Practice (Suzanne Weenink), Domenico Mangano & Marieke van Rooy, Raja’a Khalid, Lisa Tan, Tromarama, RA Walden and Anna Witt. The artists in 84 STEPS have been commissioned by Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy and Rosa de Graaf, with Wendy van Slagmaat Bos and Julija Mockutė. The programs within 84 STEPS include Trainings organized by Aqueene Wilson and Veronika Babayan, as well as Forums, Workshops, and myriad events organized by Vivian Ziherl, Jessy Koeiman, and Julija Mockutė. These activities involved a range of participants, from health experts and art historians to movement and wellness practitioners to healers and activists.

Rūta Adomaitienė: Friend My Muse at Gallery Artifex

June 2022

Special thanks to Rodion Petroff

To weave a rug by hand, the artist must lock themselves in a studio in front of the loom, and knot after knot, for months, or even years, progress little by little. According to the myth of the artist and their sources of inspiration, it seems like they should be isolated, especially when making something meticulously with their hands. With Friend My Muse, Rūta proposes a different approach to her creativity: the weaving process is the same, the sheep are the same, but the artist is not alone.

Twenty years have passed since Rūta made her last tapestry, and now she comes back to the loom with muses. The tapestry is made through the touch of only her own fingers, meditatively tying each knot, but the inspiration comes through connection with others: friends, from textile study mates like Daiva Zubrienė, Gražina Aleksandra Škikūnaitė, Ramunė Gutauskaitė-Žutautienė, to Solveiga Gutautė, an artist who is peeking through together with Rūta in the image of the rug.

The image is also inspired by another source - it was made based on a capture of artist’s Rodion Petroff’s installation Face 2 Face (2018), which is also presented in the exhibition. Friend My Muse addresses creativity as a process that happens not in a vacuum, but through connections and contact with people, art and the material world. The image, seemingly pixelated, draws connotations with a face call, isolated and glitchy. The contrast with the warm and natural wool, and the contextualization of the work reflects the feminist and grounded practice of the artist, and invites the viewer to get to know her muses and become friends as well.

About the artists:

Rūta Adomaitienė is an artist, art therapist and a mother of four children. Rūta graduated from textile at the Art Academy in Vilnius in 1995. and in 2007 became a nurse, working as one for 13 years. In 2021 she graduated with an MA in Art Therapy from Lithuanian Health Sciences university, and works as an art therapist at Ąžuolyno Klinika.

Rodion Petroff is an artist and a painter, who creates and works in Klaipėda. In 2011 he finished his Masters at the Art Academy in Vilnius, and has had more than 10 personal exhibitions and participated in more than 30 group shows in Lithuania and abroad.

Making the Tapestry

Rūta’s contact with the world is created through touch: of the sheep, of the thread, and of the tapestry. She weaves the rug by hand, knotting one knot after the other. To make such a tapestry, one has to first make a foundation: fasten strong linen threads, on which the knott will be made on the looming frame. Then, starting from the bottom, knots are made, with threads and combinations of them chosen according to the design of the tapestry. The length of the process depends on the size of the rug, the thickness of the thread, the density of the knots, and on the skill and speed of the loomer: it can take from months to years. Friend My Muse (2022) took 2 years. The artist finds looming meditative: choosing a thread, knotting it, cutting, choosing a thread, knotting it, cutting… puts her in a trance, making time fly by.

For all of her tapestries, Rūta uses natural, un-dyed wool, most of which she sheared off the sheep herself. The color of the wool comes from different breeds and the age of the sheep, as some of them are born black and fade from the sun to grey or white. The artist shears the sheep, washes the wool, and then has the wool carded (brushed out). Out of the carded wool threads are spooled, and looming can begin.

Friends Muses

‘Friend My Muse’ (2022) is the first tapestry of Rūta after a 20 year break. It can be very difficult to start after such a long break - just like starting from the beginning. The artist attributes the inspiration to start looming again to her friends. Rūta went to the quadrinialle ‘Q19: Memorabilia. To Record Into Memory’ together with Solveiga Gutautė, who is visible in the tapestry together with the artist. There, in an exhibition ‘Non-Recording Medium’ they took a picture of themselves in Rodion Petroff’s installation ‘Face 2 Face’ (2018). This picture became the basis for the design of the rug, which is why the artist invited Rodion to join this exhibition with the same installation.

Contact with others - friends and art works - inspired the design of the tapestry, and continued in the making of it. In the beginning, to make the foundation, and at the end, to take the finished rug out of the frame, Rūta invited her study mates to help out: artists Daiva Zubrienė, Gražina Aleksandra Škikūnaitė and Ramunė Gutauskaitė-Žutautienė. Contact with people and art inspired Rūta to come back to making art, and the looming of the tapestry inspired to renew old connections. ‘Friend My Muse’ - is a suggestion to see and join creativity as a web, which weaves different contexts and encourages contact.

Diana Halabi: Delivered home with no eye contact at Growing Space Wielewaal

Summer 2020

They say it takes three years to feel at home in a new place. Where is your home in those three years then? And what if the home you left doesn’t exist anymore? And how does constant contact on the phone with the old home affect our connections?

With natural and unnatural disasters, economic and social displacement, many people who have left their hometowns for a better life (or just the possibility of it) lose the home as they know it from their previous life, while not yet having rooted themselves in their new place. Having the sense of home is feeling like you belong, and only when one feels like they belong, they can contribute to their surroundings. Being elegant is something that is reserved for those who feel at home. (Diana Halabi)

The cell phone is an extension of one’s being, and what we see on the screen shapes us as much as what we see through our windows. The need for staying connected in distant times divides lives geographically, both preventing new roots to come in, but also mystifying the old ones. We talk to our friends and relatives left behind, but we never really look into each other’s eyes, making the contact superficial, but a life line still.

Diana freezes this feeling of limbo by painting screenshots of her calls with friends and family left in Beirut, while she calls them from her new place, which is not yet home, Rotterdam, and seeing what was once home change before her eyes.

Installation by Bruno Neves and pictures by Steven Maybury

Interview with Diana Halabi

[15:43, 9/24/2020]

Julija: Can you really see someone through a screen?

Diana: Not really, a screen speaks more of where we are, more than whom we are, or how we are. It is tiring to have this reality, but it is much better than having to travel to do my masters in fine arts in 1900 for example, where I would be sending my friends and family letters only, which would be nonetheless very valuable, but at the same time very ghostly.

Julija: Why do you facetime instead of calling?

Diana: I need to see people in their settings, I need to show them my surroundings too, I

don’t want any of us to become like a ghost stuck in a labyrinth of memory. But unfortunately, even though I video call,when I want to look into their eyes, I still find myself looking at their eyes and never in their eyes. The impossibility of eye contact in the video call leaves you with the imperfections of technology and confronts you with the reality of distance. And a phone can never break that distance, and we find ourselves neither here nor there. And this is exactly why I decided to paint those video calls, I used to say that whoever didn’t migrate or live abroad or never has been a refugee, can never understand what is it to have the dominance of this rectangle format of socializing (the video call) in one’s life, but then the Covid-19 pandemic came to our lives, and almost everyone became a migrant in their own homes, having video calls almost all the time.

Julija: What role does the phone play in how you see where you belong?

Diana: The phone is a blessing and a curse at the same time, everything related to it made me have dual realities at the same time. Thinking of when the 17 October revolution took place in Beirut in 2019, I was just 1 month 17 days in Rotterdam, very fresh in the city, and seeing what was happening in Beirut was heartbreaking. My phone was in my hands all the time, even in the seminars, I was refreshing facebook every minute to stay connected to what is happening in the streets of Beirut. So the phone can split one’s life into two places, which is both beautiful and exhausting. I once asked my friends to have a video call with me from inside the protest, so physically I would be walking in the streets of the Netherlands, and people greeting me with a smile (if it is sunny and they are in a good mood) and in my phone I am looking at tear gases and people running for their lives. Disturbing no?

Julija: Very! Where is your home now then?

Diana: I didn’t think that this question would be so hard to answer. Since I arrived here in Rotterdam, one year and one month ago, I haven’t visited my hometown yet, and a lot has happened since I left: a revolution, inflation, a Blast that killed over 300 people and injured thousands, and destroyed half of the city (my home included), and a pandemic. So where is home? Is it here in a city where I am still trying to find my favorite café in? Or my favorite cheese? I don’t think so yet. But is it then in a city that changed so much since I left? I am afraid to know the answer. I am as well afraid of visiting, because perhaps I don’t want to have an answer to this question, because the answer might be I have no home anymore, until further notice.

In Poland, David Bowie Was a Woman at Van Abbemuseum

Summer 2018

In Poland, David Bowie was a woman presents an inquiry into designing post-post-Soviet identity. Eight young artists and graphic designers, who grew up in Eastern Europe but now live in the West, present posters based on their own individual experiences, depicting their contemporary identities.

During communist times identity was constructed by the state, designed by constructivists for whom the reproductive quality of graphic design and print made it the art of the Soviet people. When design and art becomes a practice and statement of individualism, when identities and their signifiers are blurred and borders between East and West loosen up, what makes up our identities? Izabela Trojanowska, an 80s pop star in Poland, with her red stilettos, predatory hair and puffed shoulders can be seen as a symbol of the shift to porous identity, and the possibilities of playing with gender, national and political belonging.

The artists involved in this exhibition were: Aigustė Mockutė & Ellis Main, Anna Nana (wrs_thg), Annija Muižule, Katerina Sidorova, Ksti Hu, Leeza Pritychenko, Laimonas Zakas, Misha Gurovich and Miša Skalskis.